Special to Texas Border Border Business

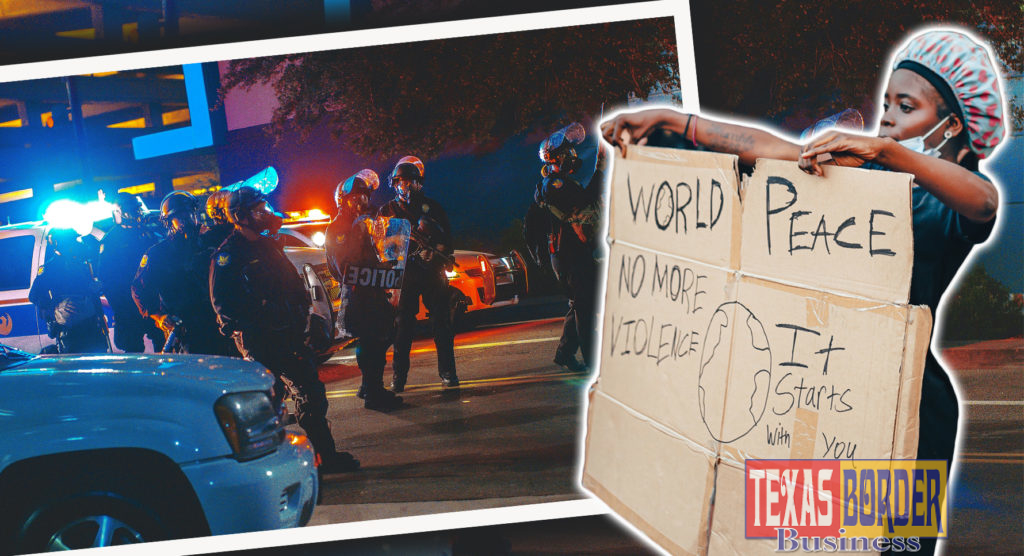

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas – With national attention focused on the use of force by police, research done by a team at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi proposes new processes police agencies can use to build more productive relationships with the communities they serve.

Working with the Aransas Pass (Texas) Police Department, Dr. Wendi Pollock, Dr. Eric Moore, and Dr. Sarah Scott, all associate professors in the Department of Social Sciences studied police interactions with the public.

Aransas Pass, in the Coastal Bend area of South Texas, has a population of about 8,300. The community is 49% Latino with a very small African-American population. The Police Department has fewer than 30 officers, three of whom are female. While the crime rate has slowed in recent years, the Aransas Pass Police Department still reports high levels of drug- and gang-related crime in the area. The department was an early adopter of body-worn cameras for officers.

“Some police departments have been using officer camera footage for some time,” Pollock said. “Researchers have largely only been interested in whether those cameras reduce complaints by citizens against the police. We thought that the cameras could do more than that.”

In a paper published May 12 in the Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles, the research team proposed that such camera footage could be used by police leaders to implement Problem Oriented Policing (POP) to address police behavior issues.

“Since the 1990s, the police have often used Problem Oriented Policing to deal with crime problems,” Pollock said. “The main idea was that instead of just responding to calls for service once a crime has already occurred, they would actively scan for problems and patterns of problems in their cities or towns.”

Police would note where they get repeat calls for service, especially for similar types of crimes, then analyze the problem.

“That may mean talking to each other, the community, and/or reviewing reports to better understand why crime keeps happening at that location and looking for underlying connections,” Pollock said.

Using what they learn, police would respond to the problem, likely in collaboration with the public, to address underlying conditions that may draw a particular type of crime to that location.

“Then they would assess whether their solution or response worked,” Pollock said. “Did that crime reduce in that area? If not, then back to analyzing the problem, but if so, then it served as a proactive way to address crime.”

This new approach could make a big difference in today’s sometimes tense police/community relationships.

“The biggest issue that the public wants the police to deal with right now is police behavior itself,” Pollock said. “The public is demanding that police treat everyone consistently, regardless of race, gender, etc., and they want accountability when there is evidence to the contrary.”

Officers who began their careers using POP to fight crime problems are now police managers, and they are used to addressing problems using data and specific, customized solutions, Pollock said.

“This is the idea behind our current research,” Pollock said. “The problem of inconsistent treatment of Black Americans (and other racial minority groups) by police has happened in many jurisdictions across the country, but the relationship between the police and their local communities are very specific to each area. The racial breakdowns, the languages used, the crime issues faced, etc., make each community unique. Therefore, the police/public interactions are also specific and unique to that location.”

As researchers who are not affiliated with a particular police department, the Texas A&M-Corpus Christi team could work with police agencies from an independent perspective.

“We could be granted access to the camera footage, look at a random sample of videos, and then give the police department a full report on the nature of any police/public interaction problems, including in those interactions where there was no ticket or arrest, and the citizen did not make a complaint,” Pollock said.

Pollock said assessments like these – known as problem analyses – would show how often force was used in any jurisdiction, as well as how often tickets were written, arrests were made and other details. In addition, it would examine whether any particular group was more or less likely to receive sanctions or actions.

“Researchers could also look at extra-legal factors such as the way officers speak to individuals of different races, genders, sexual representations or orientations, etc.,” Pollock said. “It could identify any potential legal or public relations issues. Training could be created using footage from the officers’ own departments, which is known to be more impactful. In addition, through a media release, the public can have access to the research report and that increases transparency into the actions of their local police. It may also improve trust to let them know that an outside team is reviewing the police, and they are not policing themselves.”

The team is in discussions with the Aransas Pass Police Department to survey the public about how they view their police department since the initial assessment results have been released. They also are interested in discussing performing problem analyses for other agencies in this area with the ultimate goal of helping improve the way police interact with their communities.

“The police should serve every member of their community consistently,” Pollock said. “In many cases, they do, but it is vitally important to continue to review for problems and to stop those problems before any more members of the public are harmed.”