Texas Border Business

US Chamber of Commerce

By: Stephanie Ferguson

Director, Global Employment Policy & Special Initiatives, U.S. Chamber of Commerce

Jenna Shrove

Executive Director of Strategic Advocacy and Advisor to the Chief Policy Officer

Isabella Lucy

Graphic Designer, U.S. Chamber of Commerce

The dynamics of the U.S. labor market have been changing rapidly over the last three years, but the undercurrents of those changes have been flowing for decades. The American workforce is becoming older, more diverse, and better educated. Employers are adding jobs while investing in new technologies but continue to struggle finding skilled talent. These changes will have lasting effects on employment and business operations.

Here’s what the latest data says—and what businesses need to know—about the workforce of the future.

The U.S. continues to battle a years-long labor shortage. The total number of working Americans has surpassed pre-pandemic levels, albeit at a slower growth rate than much of recent history.

Specifically, there are 167.8 million people in the labor force today. That number is expected to grow to 169.6 million over the next 7 years.

Workforce participation will be lower

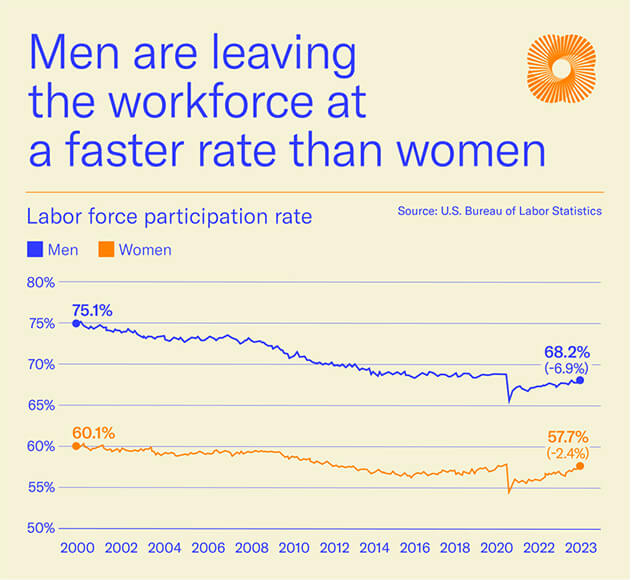

Despite this growing number, the labor force participation rate has trended downward for more than 20 years with no plateau. In 2000, the labor force participation rate for men reached over 75%, while women’s rate hovered around 61%. In 2020, men’s and women’s annual average LFPRs dropped to 67.2% and 56% respectively. The participation rate is climbing back upward but lags by 6.8% for men and 3% for women from the 2000 rates.

As we saw in the pandemic, women, by and large, leave the labor force to take care of children or loved ones. Explanations for the decline of labor force participation for prime age men (ages 25 to 54), vary, including skills mismatch and going to school.

The reality is that the labor force participation rates are unlikely to fully recover. In fact, experts estimate that the overall labor force participation rate will drop to 60.4% in 2030. Nearly three full percentage points less than the February 2020 rate.

There are many factors behind the insufficient labor force participation rate. Read more in the America Works Data Center.

The workforce is aging

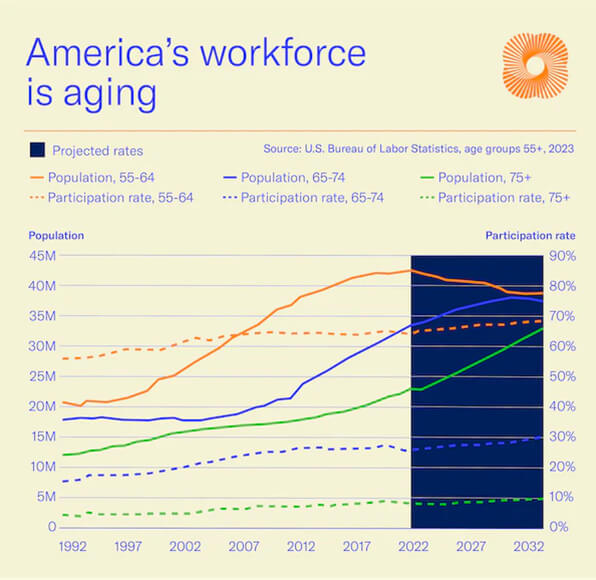

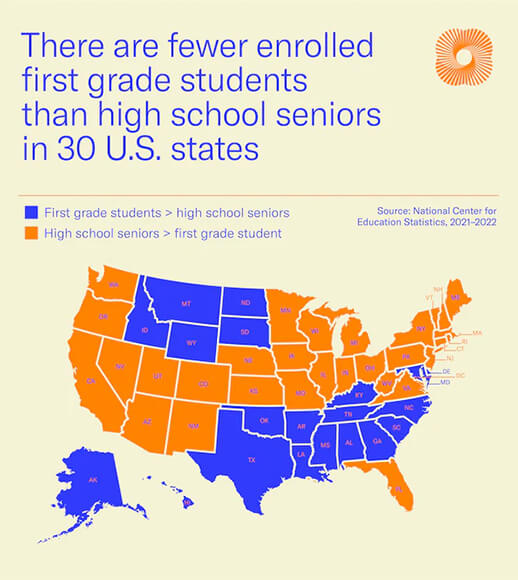

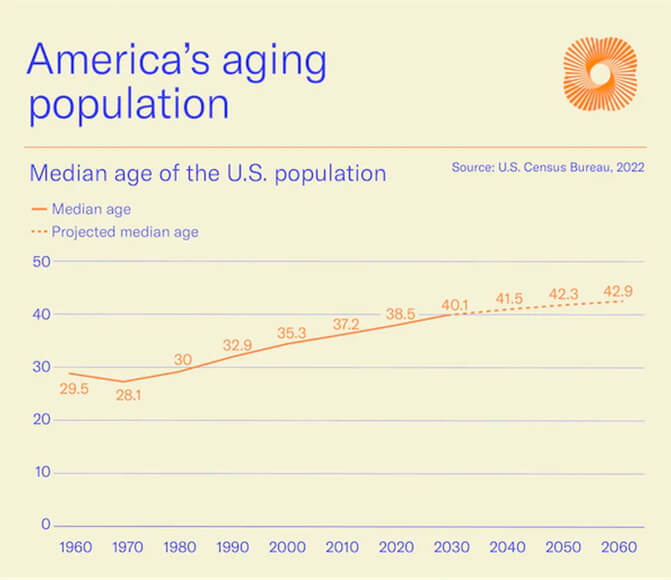

The share of older individuals within the U.S. population is steadily increasing and it’s likely this trend will continue. This shift is partly attributable to the fact that younger generations are having fewer children compared to their predecessors, resulting in a progressively older, and diminishing population.

Following the Great Recession, birth rates in the U.S. experienced a decline, ultimately reaching a historic low in 2020. Unfortunately, these rates have not shown signs of recovery. This persistently low birth rate is causing the U.S. population to age at an accelerated rate.

Over the past two decades, there has been a remarkable 117% increase in the number of workers aged 65 or older, and it is projected that the number of workers aged 55 or older will grow three times faster than the number of workers aged 25-54.

As these older workers eventually retire, businesses will encounter challenges in filling job vacancies with a less experienced workforce, potentially exacerbating the shortage of workers to support the expanding economy. Consequently, the nation as a whole will be tasked with providing care and support for a growing number of elderly Americans.

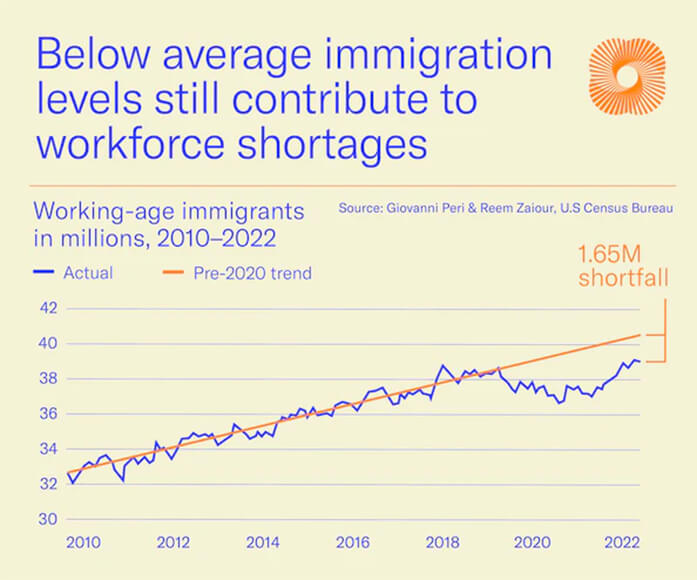

The workforce will need more legal immigration

Fewer legal immigrants coming to the U.S. means that critical sources of talent for American businesses are drying up, contributing to the significant workforce problems companies are currently facing. Many of tomorrow’s innovators are today’s foreign national college students in the U.S. But these numbers have slid as well.

U.S. Census Bureau data shows that net international migration to the U.S. only contributed to a 247,000 person increase to the U.S. population between 2020 and 2021. Compared to the prior decade’s high of a 1,049,000 increase in our population between 2015 and 2016 due to immigration, the impact that immigration has had on U.S. population growth dropped by 76%.

Women will outnumber men

Current demographic trends indicate that the ratio of men to women in the workforce is heading towards parity. Women now account for 46.8% of the labor force, and this number is predicted to rise to 47% by 2031.

While women are 5 to 8 times more likely than men to have their employment affected by caregiver responsibilities, women’s workforce participation has rebounded since the pandemic lows.

But aside from how many women are participating, there is also a considering of wherewomen participating in the labor force. Industries that are historically comprised of a large female workforce—health care and education—are growing at faster rates than male dominated industries.

More women are completing degrees today than ever before. In 2018, 65% of women who began their degree in 2012 had graduated, compared to 59% of males. Women continue to earn degrees at higher rates than men and are expected to account for 57% and 60% of all Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees earned, respectively, in 2029.

Women are also climbing the corporate ladder. The number of women in Senior VP positions and C-Suite positions have climbed by 3% and 5% respectively since 2016

The workforce will be increasingly diverse

The U.S. is projected to become more diverse in 2045 as diverse Americans are projected to account for 50.3% of the population. The populations of Black, Asian, and Hispanic Americans are all expected to rise, with Hispanics anticipated to account for 30% of the labor force by 2060. This is due to higher labor force participation and birth rates.

While the workforce is becoming more diverse as a whole, diversity within industries is not keeping pace. Black workers are underrepresented in the tech industry and especially in the roles with the fasted projected growth. Similarly, there is an underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic workers in the STEM fields. Without intervention, the national decline in math and reading scores in our public schools could further narrow the future diversity within the STEM workforce and the nation’s broader ability to compete on the international stage.

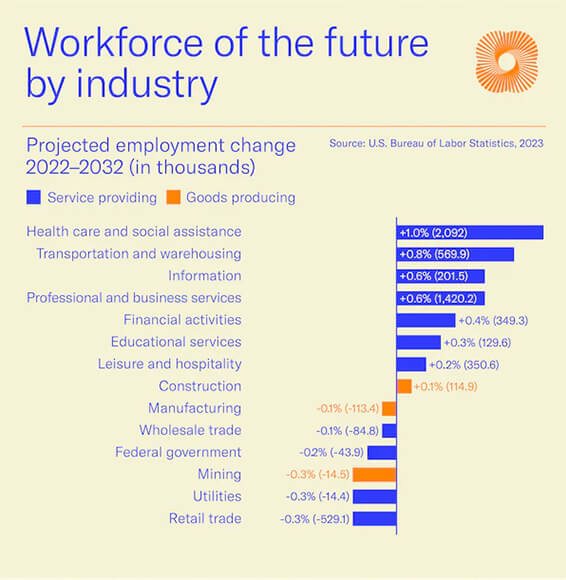

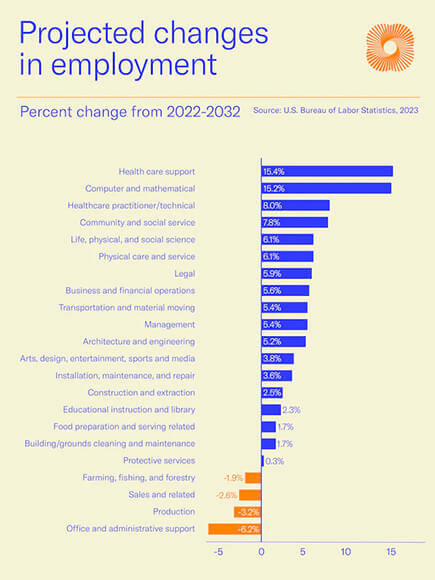

Some industries will have a larger workforce

Slower employment growth is projected in goods-producing sectors, with the construction, manufacturing, and mining sectors seeing the slowest growth—or highest shrink—among them. Increasing automation, combined with international competition, is expected to limit employment demand in the manufacturing sector and in many of the production occupations concentrated in this sector. Changing consumer preferences and increases in the use of technology are expected to lead to declines in employment in the postal service, retail trade, and utilities industries.

Structural changes introduced by the pandemic, such as higher demand for information technology (IT) services to support expanded telework, are expected. The emergence of widely available artificial intelligence is also anticipated to create new jobs in the IT sector and others.

Conversely, American families and businesses are becoming increasingly accustomed to tapping into services for health, education, entertainment, and daily activities. For this reason, the service-providing sectors are expected to account for most of the jobs added from 2020 to 2032.

The U.S. will also require greater resources to care for our aging population. Therefore, it is expected that there will be a greater demand for healthcare and pharmaceutical workers. Specifically, over one-quarter (3.3 million) of new jobs in the next seven years will be in the healthcare and social assistance sector. However, forecasts show significant shortages of healthcare workers like nurses in over half of U.S. states by 2026.

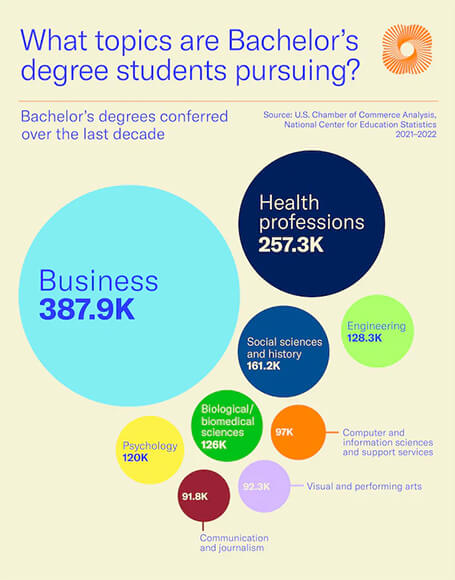

In 2015, the oil industry workforce boomed with more than 14,000 students seeking petroleum-engineering degrees. But now, students’ worries about climate change and the instability of jobs in the oil industry—despite record profits—are contributing to declining interest.

Despite the demand for talent in the technology, healthcare, and oil industries, degrees in business continue to outpace other majors by far. Healthcare is a close second, with social sciences coming in third.

The workforce will be well-educated

The makeup of the future workforce is linked to trends in educational attainment. For example, in March 2020 employment rates were highest among 25- to 34-year-olds with bachelor’s degrees or higher (86 percent), followed by those with some college (78 percent), high school graduates (69 percent), and those without a high school diploma (57 percent).

Notably, over the past 24 years there has been an increase in the U.S. labor force’s education levels. The share of individuals holding Bachelor’s degrees and advanced degrees has steadily expanded, rising by 7 and 5 percentage points respectively, from 1992 to 2016.

At the same time, the share of individuals with lower educational attainment, such as those without a high school diploma or only a high school diploma, has diminished by around 5 and 10 percentage points respectively during the same period.

Recent years have seen fluctuations in labor force participation rates among groups with varying educational attainment. The labor force participation rate for those without a high school diploma has remained relatively stable. However, participation declined by 3.1% for those with Bachelor’s degrees or higher, declined by 5.1% for those with some college or an associate degree, and declined by 4.5% for high school graduates.

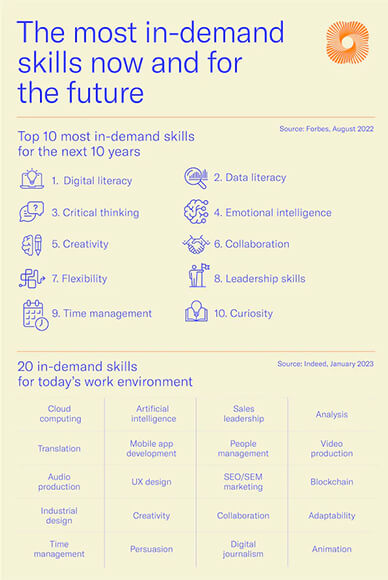

The workforce will need new skills

Navigating the imminent future of the workforce demands a need for continuous skill development. As articulated by U.S. adults, staying attuned to shifting workplace dynamics necessitates ongoing training and upskilling. This will be necessary, as the majority of individuals intending to retain their roles in the near future will need to upskill and reskill.

Employers underscore the value of dependability, teamwork, problem-solving, and flexibility. Proficiency in synthesizing messages, adapting to uncertainty, and exhibiting self-confidence correlates with improved employment prospects, higher incomes, and job satisfaction.

At the same time, a global survey unveiled deficiencies in software use, development, and digital systems understanding. As the landscape evolves, employers must proactively invest in reskilling to harness the full potential of the workforce and ensure a prosperous future.

Conclusion

In summary, the future of the U.S. workforce is undergoing significant changes. We see a smaller, yet more diverse population, along with challenges in labor force participation rates and a growing emphasis on education and skills development. Industries are in transition, with the service sector gaining prominence and grappling with a pressing need to address shortages, particularly in vital areas like healthcare. Immigration remains a critical factor in talent acquisition. To navigate these transformations successfully, it’s crucial for businesses, policymakers, and educational institutions to adapt and collaborate effectively for a prosperous workforce in the years ahead.