Texas Border Business

By L. Boyd Finch, Handbook of Texas Online

Published by the Texas State Historical Association

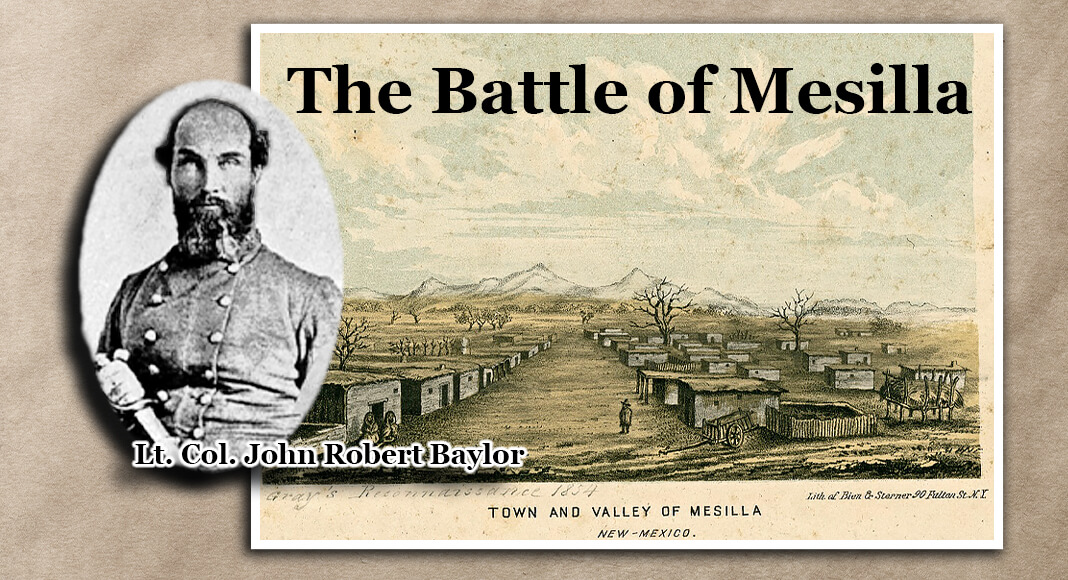

On July 24, 1861, Lt. Col. John Robert Baylor led 300 men from Fort Bliss forty miles up the east bank of the Rio Grande to Fort Fillmore, New Mexico. With him were two companies of the Second Texas Mounted Rifles, a Texas light-artillery company without its howitzers, an El Paso County scout company, and some civilians. The Texans reached the vicinity of Fort Fillmore at night and placed themselves between the fort and its water supply at the river. Baylor canceled a planned attack after learning that one of his men had warned the garrison. His Texans forded the Rio Grande and early that afternoon entered nearby Mesilla, a strongly pro-Confederate community. With 380 infantry and mounted riflemen, plus howitzers, Union major Isaac Lynde approached Mesilla from the south on July 25. Baylor rejected his demand for surrender, and Lynde ordered his artillery to open fire. After three Union enlisted men died in a bungled charge and two officers and four other men were wounded, Lynde ordered a return to the fort. The Confederates suffered no casualties but remained in Mesilla, fearing a trap. Baylor sent to El Paso for artillery and additional men. When he found out that Baylor had sent for artillery, Lynde ordered the fort abandoned that night. Because Baylor blocked the shortest retreat route, north up the Rio Grande toward Fort Craig, New Mexico, the Union garrison headed northeast toward San Augustin Pass in the Organ Mountains.

At sunrise on July 27 Baylor discovered Lynde’s withdrawal. Baylor’s troops and some “Arizona” civilians gave chase. By the time Baylor’s speediest horsemen caught up with the stragglers, the roadside was littered with discarded equipment and prostrate regulars begging for water. Lynde and his mounted troops reached San Augustin Springs, on the far side of the pass, and attempted to send water back to the lagging infantry. Baylor with part of his command crossed the mountains by another pass and early in the afternoon of July 27 rode unopposed into Lynde’s temporary camp. After a short discussion, Lynde surrendered his 492-man force, despite objections from many of his officers. The only casualty was one Union soldier killed as he threatened a Confederate. The size of Baylor’s force was presumably smaller. Baylor proclaimed Arizona Territory, Confederate States of America, in Mesilla on August 1 and named himself governor. He remained in the area until the spring of 1862, several weeks after Confederate general Henry Hopkins Sibley arrived with three regiments of Texas Mounted Volunteers. The victory at Mesilla was one of the war’s early and surprising Confederate successes. Baylor’s dashing actions of the summer of 1861 added to his fame as a folk hero.