Texas Border Business

By Amanda A. Taylor-Uchoa

RIO GRANDE VALLEY, TEXAS – If you were to search for “piñatas” within some of the largest museum search engines, such as The Getty Museum, you’d be lucky to find a handful of images. In fact, the piñata is categorized simply as a vessel, found right alongside Greek vases, and not as a form of Mexican American art.

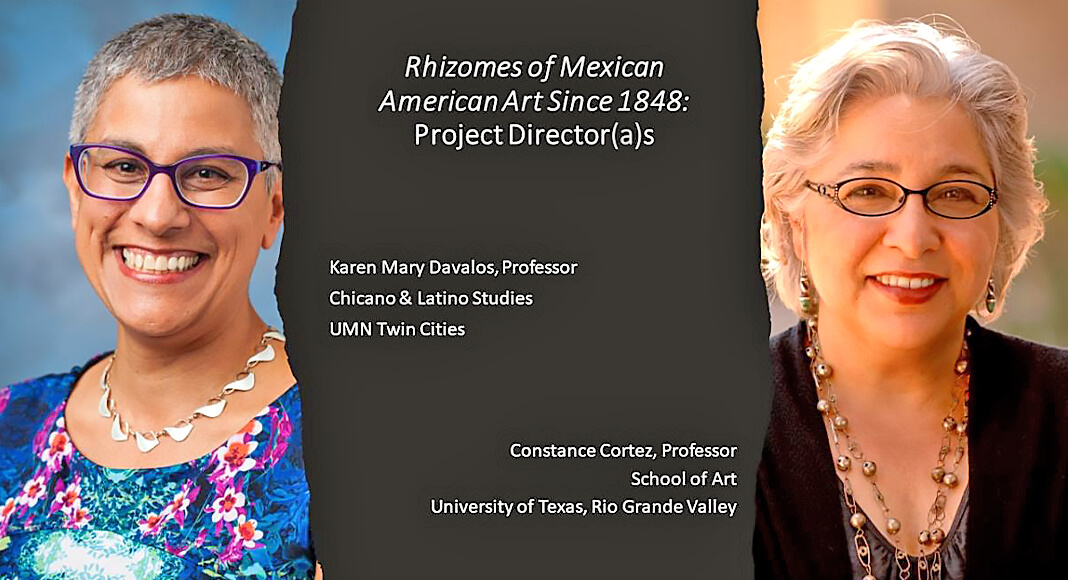

Constance Cortez, professor of Chicana/o Art History and Post Contact Art of Mexico in the UTRGV School of Art, said this lack of information happens because most major museum search engine software strictly uses an English lexicon in its searches.

“It’s a huge, huge problem,” Cortez said. “This happens with a number of things that are generated with Mexican American arts – they don’t fit within this Eurocentric lexicon that museums use. Unless you know that about that particular software system all these museums use, you’re not going to find anything on particular pieces of Mexican American art.”

To help remedy this disparity, a special project entitled “Mexican American Art Since 1848” was created by co-founders Cortez and Karen Mary Davalos, professor of Chicano and Latin Studies within the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities.

“Mexican American Art Since 1848” is a digital portal that progressively aggregates Mexican American art and related documentation from dozens of digital collections in libraries, archives and museums throughout the United States.

It is a multi-component system that will help resolve the misunderstandings and invisibility of visual arts by Mexican American artists, often considered a “dispossessed community.”

“Mexican American Art Since 1848” will enable users to search through collections of Mexican American art housed at partner institutions, making it easier for users to search through digitized collections of art that remain hard to find.

The goal for Cortez and Davalos is that the portal will encourage more research and teaching on the breadth and scope of artistic work by generations of Mexican heritage artists, and that those interactions will benefit partner institutions with attention, acclaim and funding opportunities.

“It works like a post custodial database,” Davalos said. “That means the user gets sent back to the original location of this item that we’re sharing. And that’s intentional, because we’re trying to challenge these colonial legacies of stockpiling and extraction by saying that I own this stuff, when it’s not really owned by anybody except the artist.”

ACCESSSING THE ECOSYSTEM

The portal compiles digital information from libraries, archive and museums, housed through the UMN website. You can search through the portal as you would a regular search engine, but the database is designed to virtually unite the seeker with digital files of Mexican American art from libraries, archives and museums.

It is open to all students, scholars, educators and the public, free of charge. The portal links collections and makes harvested information searchable from a specific location, so the time it would take to search for a piece of Mexican American art is far less than using a larger museum database.

Launched in 2021 with support from the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS), the first iteration of the project included compiling content for existing state and national compilers, such as Calisphere, The Portal to Texas History, the Smithsonian Collections Search Center, and the Digital Public Library of America. A repository of digitized documents was made accessible by the International Center for the Art of Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston.

“The first phase of the project was to incorporate all of these set archives,” Cortez said. “We have incorporated, so far, 20,000 digital records. And we’re talking about paintings, prints, murals, textiles, lowrider cards, cars – art which wouldn’t necessarily be shown by museums.”

A second iteration to the project shares newly digitized art and related materials from partnering museums such as the National Museum of Art in Chicago, the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque, and Mexic-Arte Museum in Austin.

THE RHIZOMES INITIATIVE

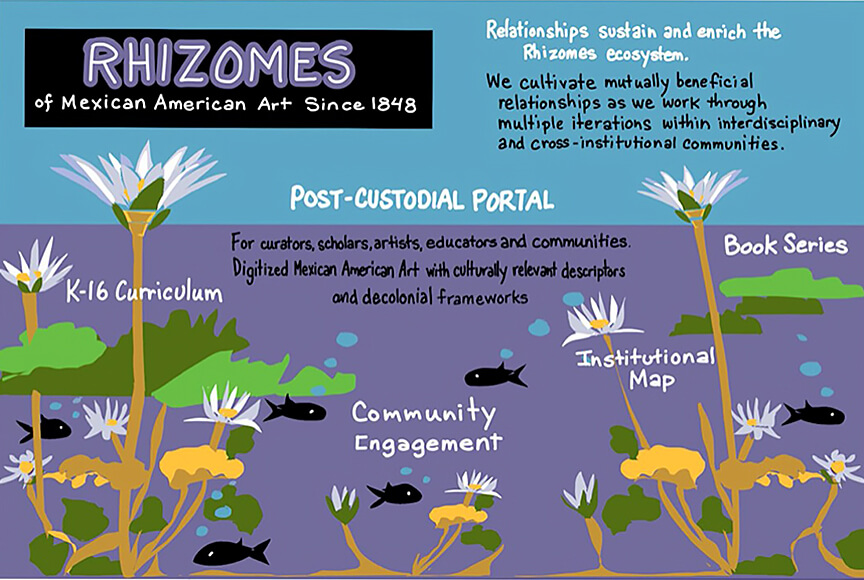

The “Mexican American Art since 1848” portal is only one component of a larger initiative: “Rhizomes: Mexican American Art Since 1848,” which includes the portal itself, a book series, K-16 curriculum, and an institutional map to visualize and help identify relevant collections across the nation.

- Book Series – Adjacent Imaginaries: Mexican American Art Since 1848 is in the works. This will be a multi-volume, full-color digital edition and physical text. Nationally, historically and aesthetically comprehensive in its analysis, the book series will examine artists’ lives and works, artist collectives, exhibitions, trends in art criticism, private and public collections, and contributions of arts organizations, diversifying American art history, and other fields.

- Curriculum and Community Engagement – “Rhizomes”supports crowd-sourced knowledge mobilization and production, such as user-created virtual exhibitions, timelines, and K-16 curricula and lesson plans. By displaying user content, “Rhizomes”supports perspectives outside of higher education, including those of bilingual students and teachers, Chicana/o/x artists, and Mexican-heritage communities.

- Institutional Map – With support from the Henry Luce Foundation, Rhizomes Initiative collaborated with RomoGIS Enterprises to develop the Rhizomes Institutional Map, which uses ArcGIS to allow users to see nodes of engagement with institutions where Mexican American art is housed: libraries, archives, museums and other collections.

FUNDING AND FUTURE COLLABORATIONS

Between Davalos and Cortez, multiple grants have been awarded for the project, including grants from Humanities Without Walls, American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS), the Henry Luce Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).

Davalos and Cortez see the project as sustainable for years to come with the help of partnering museums and future community collaborations.

“When we launched the portal, we were very excited,” Davalos said. “Now, we’re in the middle of this project that basically has no end, so it’s very exciting and it’s frightening at the same time because it’s not the kind of thing that most academics do.”

While both Davalos and Cortez are educators, in addition to co-directing the project, they believe their commitment to the database and Rhizomes initiatives will help rediscover Mexican American art that otherwise would be lost.

“It’s a long-time commitment, but we feel that it is important and it’s about time,” Cortez said. “If we can help people to understand the Mexican American presence a little bit more in the United States, then that’s good.”