Texas Border Business

University of Notre Dame, Indiana – It’s a bright morning in Hidalgo, Texas, a small town on the Rio Grande about 60 miles inland from the Gulf of Mexico. Like many border towns, there’s some history here. A defining feature of Hidalgo is the Old Pump House, built in 1909 right on the riverbank to bring water to thousands of acres of farmland in the Rio Grande Valley. In 1933, a massive hurricane flooded the area and caused the river to alter its course: The bank was now about a half mile away. A channel was built to fill the gap, until the facility aged out of usefulness in 1983.

Which is to say, things here have changed.

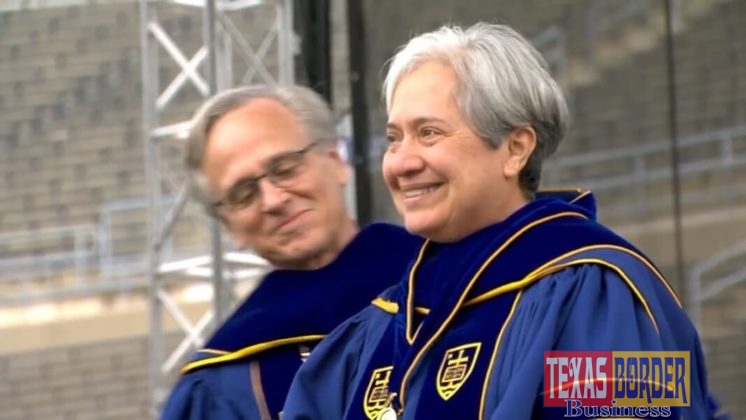

There’s another defining feature in this area: a jagged wall that separates the U.S. from Mexico. In Hidalgo, it’s about 100 yards from the pump house. It rises and falls with the topography, alternating between stretches of concrete barrier in some areas and high metal fence in others. Sister Norma Pimentel, M.J., is known to bring visitors here to pray and reflect. To her, it’s another reminder that things have changed.

“I grew up here, and we didn’t have walls,” Sister Norma remembers. “People from this side and that side, we were family. They allowed us to be in community with each other.”

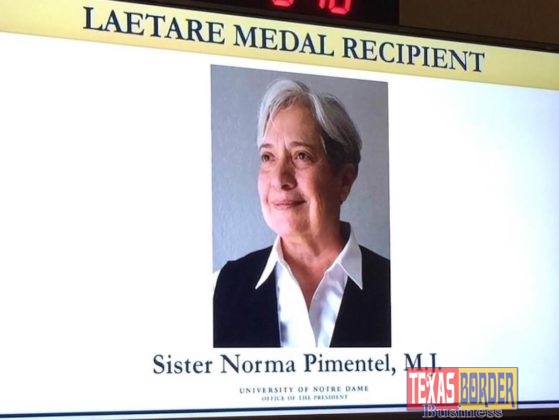

Sister Norma is executive director of Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, the charitable arm of the Catholic Diocese of Brownsville. The University of Notre Dame is honoring her with the 2018 Laetare Medal. Established at Notre Dame in 1883, the Laetare Medal was conceived as an American counterpart of the Golden Rose, a papal honor that antedates the 11th century. Past Laetare recipients include President John F. Kennedy, Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day, novelist Walker Percy, former vice president Joe Biden and former speaker of the House John Boehner. It is considered the most prestigious honor given to an American Catholic.

The “American” part of that designation Sister Norma says occurred by “chiripa — sheer chance.” Her parents came from Mexico to the U.S. in the 1950s when her father sought to become an American citizen. He filled out an application and planned to return home to Mexico to await a response, but was told he must wait in the U.S. while his application was processed. He hadn’t planned on the extended stay with young children and a pregnant wife but found work bagging groceries and an apartment for rent. During the stay, his wife gave birth to Norma. The family stayed in South Texas, but with relatives on both sides of the border Sister Norma refers to her upbringing as “entre dos fronteras, enjoying life in two countries.”

There were fewer strangers in Sister Norma’s life then. This too has changed. One of her duties is oversight of the Catholic Charities of Rio Grande Valley’s Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen, Texas, the largest city in Hidalgo County. It is here that scores of immigrants — approximately 100 every day, Sister Norma estimates — stop after crossing the border into the U.S. They arrive after processing by U.S. Customs and Border Protection with little more than the clothes on their backs and a notice to appear in immigration court. In many cases, they’ve turned themselves in to the border patrol as an initial step in seeking asylum in the U.S.

“They come totally destroyed,” Sister Norma says.

“They’ve come through so much. They’ve come from different countries in Central America, up through Mexico, most of the time walking and hiding from people who want to hurt them.”

The journey from Central America to the U.S. is an arduous and dangerous one. Often immigrants will pay thousands of dollars to guides for assistance in traveling north. This may require selling off many of their worldly possessions, including mortgaging their homes in which family they’re leaving behind may still be living. But the money rarely pays for protection. They are vulnerable to every kind of harm on the journey, especially women, who are prey for rapists and human traffickers. Other times kidnappers will take children hostage and demand ransom money from the family.

Yet for these people, the risks of staying in their countries outweigh the risks of making the journey. The vast majority of the immigrants traveling through the respite center are fleeing war, crime or crippling economic circumstances back home. So they leave, becoming strangers in a strange land on their way to a friend or family member already here.

One such case is Jose, who arrived at the respite center late one afternoon with his son, Gabriel. He was the subject of increasing harassment and threats by gangs in his native El Salvador. Jose was in the army and later worked for a city mayor. His position gave him access to things like firearms and uniforms, which the gangs coveted so they could impersonate military personnel. As he continued to refuse their demands, the threats escalated. Amazingly, despite his background of military and government service, he didn’t have adequate protection from the gangs.

“My boss told me — my direct supervisor, the mayor — that I should quit my job,” Jose says. “He thought that quitting was the only way to keep my distance from them. They had already marked me, how I worked … they didn’t stop bothering me. When I was in the army, they bothered me for two years. I was just there to do my job, earn my daily bread.”

When the gangs began to threaten Gabriel’s life, Jose finally decided to leave. He left behind a wife and a 2-year old in El Salvador and traveled 25 days before reaching McAllen.

Jose and his son, Gabriel.

Stories like Jose’s have been a part of Sister Norma’s experience ever since she entered religious life. In the 1970s, the border patrol would routinely contact the superior at her convent seeking shelter for an asylee family. They would stay with the community until arrangements could be made for them to travel to family in the U.S. “During those first years of my religious formation, I quickly learned the importance of living out our faith by how we welcome and protect those that need us, especially the vulnerable stranger in our midst,” she says.

While ad hoc care for refugee families was always part of living out vocation on the border, a more systemic response to the issue became acutely necessary in 2014. In spring and summer of that year, more than 130,000 refugees from Central America streamed across the border into the Rio Grande Valley. A significant number were unaccompanied children, sent by desperate parents with groups heading north to the U.S. in hopes they would be taken in by a relative. Customs and Border Protection was overrun, struggling to provide safe shelter for such a flood of people moving in such a short amount of time.

In response, Sister Norma turned the parish hall at Sacred Heart Church in McAllen into a makeshift refugee camp. The city donated portable restrooms and showers, cots and tents. When a city worker surveyed the scene one day he asked Sister Norma what she was doing. “I’m restoring human dignity,” she said. Her work earned her the recognition of Pope Francis in 2015 during a virtual town hall-style meeting ahead of his U.S. visit. He used Sister Norma’s example as the context for saying a broad thank-you:

Refugees entering the Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley building.

“I want to thank you,” the pope said to Sister Norma. “And through you to thank all the sisters of religious orders in the U.S. for the work that you have done and that you do in the United States. It’s great. I congratulate you. Be courageous. Move forward.”

Two years later, Sister Norma joined Pope Francis at a press conference at the Vatican to launch a campaign called “Share the Journey,” organized by Caritas Internationalis. The initiative aims to help immigrants who uproot and move to another country.

From the parish hall to its current location in two adjoined storefronts in downtown McAllen, the work of restoring human dignity at the respite center remains the same. The numbers haven’t again reached the crisis levels of 2014. There was a surge in the fall of 2016, just before the U.S. presidential election, then a dramatic drop-off. In recent months, the numbers of people leaving Central America for the United States have trended upward. For people who have spent weeks traveling, on constant alert to avoid the dangers of the journey, the respite center is often the first time in a long while they’ve felt welcomed and restored.

“The families walk in and they’re amazed,” Sister Norma says.

“Sometimes they have tears in their eyes because of the joy of being welcomed. The moment they walk through that door, and they enter this room with volunteers clapping and saying ‘Bienvenidos!’ you see in their faces, this transformation beginning.”

The afternoon of Jose’s visit, about a dozen children are with the group. A young mother breastfeeds her child then lays her down for a nap in the nearby crib. After some initial shyness, the other children make their way to a fenced-off indoor play area. “All the worries about the trip stay on the other side of the fence,” Sister Norma says. “Here they can be a kid again.”

Guests rarely stay more than several hours — just enough time to get a hot bowl of soup, a shower, some new clothes and a bag filled with essentials for the rest of the journey. The center’s volunteer staff helps them contact the family member they’re on the way to see and arrange for that relative to purchase the bus tickets for the trip. Before they leave they’re handed a large manila envelope with a printout glued to it that reads, “Please help me. I do not speak English. What bus do I need to take? Thank you for your help!”

The center’s volunteer staff offers clothes and other items to refugees, and helps them contact the family member they’re on the way to see.

And each day, every day, the process repeats. Sister Norma gets a text from the border patrol, indicating how many people they’re dropping off at the bus station to be picked up by Catholic Charities, and at what time. The vans pick them up. They shuffle in. They rest. Then they’re on their way. Days with a lot of visitors are challenging, but Sister Norma doesn’t count hours. “I don’t look at this as work,” she says. “It’s my life.”

Sister Norma recognizes the work does not enjoy universal approval, especially in the current political climate. She traces this partly to the profound effect 9/11 has had here. In the aftermath of the attacks, resources began pouring to the southern U.S. border to beef up security. The wall in Hidalgo was one that was built soon after. And as physical walls went up, emotional and spiritual barriers were erected as well. The attacks caused a sizable portion of the American population to develop (or reinforce) a heightened distrust of the stranger entering the country. While there are real risks to be addressed on the border, Sister Norma believes an outsized emphasis on security can come at the cost of the merciful response children of God are called employ.

And if the physical barriers are a new reality, Sister Norma suggests the spiritual walls don’t have to be.

“They haven’t had a chance to get close,” Sister Norma says of those who oppose her work. “To see that face of that mother, of that child, and when you see that there’s a special connection that happens and you know as a human being you feel the need to reach out and help.”

Courtesy of the University of Notre Dame